PARIS — With a sloppy style of vacuous vicissitudes, Cy Twombly reversed what the avant-gardes of the prewar era held as a given: the view of history as a burden. There is a marvelously sprightly, loose and intuitive feel about Twombly’s operatic paintings that manages to merge mythic, classical intellectualism with a Dionysian sensual immoderation that verges on shit. By this playful amalgam of semiotics with scatology, Twombly redevised history painting into palimpsest poop.

Highbrow works such as “Nine Discourses on Commodus” (1963), “Fifty Days at Iliam” (1978) and “Coronation of Sesostris” (2000) organize a relaxed Pompidou retrospective containing some 200 paintings, sculptures, drawings, and photographs, mercifully hung in chronological order. It is cogently enthralling and spaciously mounted by Pompidou curator Jonas Storsve and Nicola del Roscio of the Cy Twombly Foundation. Sad to say, the show will not be traveling from Paris.

Born in Virginia in 1928, Edwin Parker Twombly, Jr. inherited the name Cy from his father — who pitched baseball for the Chicago White Sox and got his nickname after the legendary Cy Young. Following a trip to Paris and Morocco with Robert Rauschenberg, whom he met as a student and accompanied to Black Mountain College for the summer of 1951, Twombly expatriated to Rome in 1957, where he pressed further into his emulsified and rickety style. An uninhibited use of sallow colors is already evident in “Untitled (New York)” (1954) (that opens the show) and “Volubilis” (1953). “Volubilis” is named after the partly excavated Berber and Roman city in Morocco situated near the city of Meknes and commonly considered the capital of the ancient kingdom of Mauretania. The scratchy, scribbled dribbles that “Volubilis” employs owe a lot to a less solemn, that is, transgressive, approach to Abstract Expressionism. Indeed, Twombly’s work’s quintessence is Epicurean and festive in nature — and he never much conformed to Ab Ex’s angst. Yet I felt something like twinges of existential doubt or futility while appreciating the spiky fertility of “Volubilis,” something Twombly most likely absorbed from his early passion for the transubstantiating drawings of Alberto Giacometti.

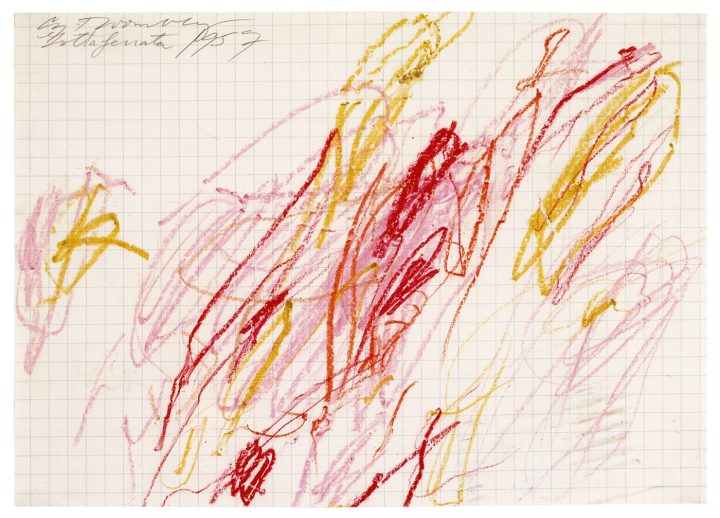

From the same year, there is also a suite of seven child-like, wax crayon drawings that Twombly gave to his friend Betty Stokes, who was married to Venetian aristocrat Alvise Di Robilant and had just given birth to their first child in Grottaferrata (from where the drawings take their name). To make them, Twombly took liberties with the liberty that André Masson’s experiments with automatic drawing yielded in the 1920s. There is also a never-before-seen sweet suite of drawings he made in bed, in the dark at Grottaferrata, that feature repeated, spewing hump-forms suggestive of volcanic eruptions, like the one that buried Pompeii in ash.

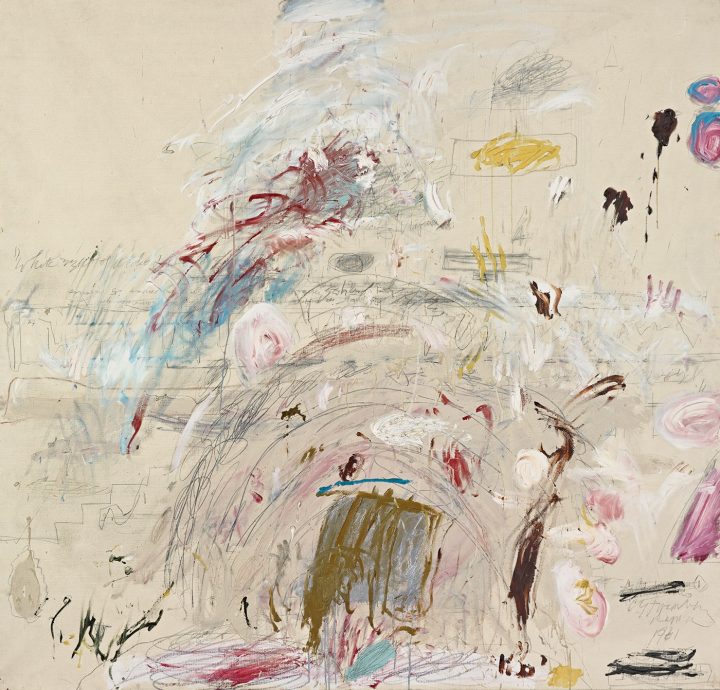

The most accomplished post–Ab Ex paintings (resembling a bit, Arshile Gorky’s) are those that also engage with a haunting look of improvisational planned chance where chance operations are deliberately introduced into the creative process, such as the tantalizingly smudged “School of Athens” (1961), loopy and sensual “Dutch Interior” (1962) and the tasteful yet flamboyant “Achilles Mourning the Death of Patroclus” (1962). “School of Athens” and “Dutch Interior” are great examples of his almost convulsive, balm-encrusted paintings made between 1960 and 1962. This is when he created some of his hottest, most voluptuous paintings, in which churning male and female sexual body parts flutter and float through splatters and splurges that play off the thick, eggshell-whitish ground suggestive of foamy sea scum. Inspired in part by the midsummer Italian holiday of Ferragosto (rooted in an ancient Roman fertility festival) the sloppy, raunchy imagery in “School of Athens” is excessively goofy — congregating delicately scratched or scribbled shit messes against each other. Baboons might just as well have produced it.

Twombly does elegiac restraint very well too. This is abundantly apparent in the viscous paintings “Orpheus” (1979) and “Veil of Orpheus” (1968) at the Gagosian exhibition, a calm, whitish show of six large drawings and five paintings that riff on the archaic tale of Orpheus. The large painting “Orpheus” contains urgently curtailed marks that hint at the word Orpheus while refusing to move completely beyond gesture into actual readability. The same level of abstraction as applied to Greek myth is found in French composer Pierre Henry’s great musique concrète composition “The Veil of Orpheus” from 1953. With the audacious “Achilles Mourning the Death of Patroclus” at the Pompidou, we have before us a large, luxuriant canvas without the typical framed glass barrier so many other paintings here are burdened with. I guess that when these babies sell for around 70 million dollars a pop (as they do) the owners are willing to kill their surface sensuality a bit in the interests of safety. Anyway, “Achilles” conveys an immediate soft-hot, violent (or vigorous) sensual attractiveness — while also remaining curbed. The subject, a reference to Patroclus from Homer’s Iliad, is typical of Twombly’s playful interest in Mediterranean myth. His use of restrained pencil lines and two warm orgiastic marks in “Achilles,” akin to scrawled vandalism, compares favorably to Anselm Kiefer’s pious and heavy resurrections of epic battles and ancient myths that were also presented at the Pompidou not long ago, to less effect.

What distinguishes “Achilles” is its sliding signifiers — the way it correlates a gooey gestural present with an imperturbable, passive, classical past. It also has immediacy. Its seemingly unpremeditated gestures suggest the eternal presence of the now, because Twombly neither accepts the Greek classics as a perfunctory accumulation of events — succeeding one another in time — nor as a reservoir of fixed forms. Rather, especially in “The Vengeance of Achilles” (1962), he seems to have positioned self-possession on the tip of a bloody spearhead, piercing history with a slippery and alienated here-and-now present. At the same time, his slathering and slack markings, such as in “Dutch Interior,” suggest a willful regression into the infantile, so as to move the viewer closer to sensual instinctiveness. Yet the baby-playing-with-poop regression sensed in “School of Athens” is turned out as optimistic: it projects historical confidence at the same time, by piggy-backing on Raphael’s Italian Renaissance “The School of Athens” (1511) frescoes.

Large-scale synthesis of words and images and sophisticated soft lighting propel that confident feel in the fantastically installed “Fifty Days at Iliam” (1978), a 10-part painting cycle based on Alexander Pope’s translation of the Iliad, on loan from the Philadelphia Museum of Art. I was especially moved by the carnal, crimson canvas “The Fire that Consumes All Before It” (1978). Anticipating neo-expressionism by allowing color to become dissociated from line, Twombly’s self-imposed blundering here is far more elegant and earnest than Julian Schnabel’s bombastic combinations of scribbled words and abstract marks would ever be.

As denigrated in Donald Judd’s art criticism, I found less successful the swarming, faux urgent “Nine Discourses on Commodus” (1963) cycle with its overripe and agitated crimson swirling brushstrokes sent hovering on a rather uniform gray ground. These works, devoted to the Roman emperor Commodus, who is remembered as a bloodthirsty ruler, were inspired by John F. Kennedy’s splattered brains when he was assassinated in Dallas. Though ersatz by comparison to “Achilles Mourning the Death of Patroclus,” I don’t deny some collective force surviving in this series of presentations of bodily sensation in disarray, but the uniform vertical gray ground tends to kill it.

Turning his gestural Ab Ex materiality towards the Minimalism and Conceptualism that emerged around the world in the mid-1960s, Twombly created a series of taut, austere, muted paintings with energetic backgrounds of grey or black inscribed with simple geometric forms in distress or script-like loop-de-loops made with white wax crayon. These works, including the windswept “Night Watch” (1966), on loan from a private collection on the West Coast, strongly suggest Joseph Beuys’s scrawled blackboards (though they lack his social idealist (leftist) intent).

White is the choice for Twombly’s sculpture assemblages that are grouped together so the Paris skyline enhances them. Even though Twombly was an early enthusiast of Kurt Schwitters’s collages, his assemblages are really not very good. Consisting of disparate found materials like wood, electrical plugs, cardboard boxes, scraps of metal and artificial flowers — and unified by a coat of white plaster — they are just too reminiscent of Picasso’s superior work in the medium. Though all his compositions straddle abstraction, Twombly is so much better, so much more richly psychic, when he stays within two-dimensional, collaged space so as to create unexpectedly affective territories where connections are made to be undone. This is evident in his rather juicy but minimalistic “Bacchanalia” (1977) cycle and particularly with the gratifying “Pan” (1975) collage. Probing the gap between sign and signified, it is a delighting feat of free association thrown up against a state of panic.

Like handwriting adorning a love letter, the title makes its way across the top half of “Wilder Shores of Love” (1985), a work alluding to the 1954 Lesley Blanch book of the same name. Thus Twombly evokes a kind of sentimental longing for other places and other times through a compost heap of past matter — now ready to sprout new forms.

Some may contest this, but for me, the Pompidou show slides unpropitiously downhill from there, as Twombly relies less and less on his emollient energetic mark making and more and more on letting gravity have its way with drooling liquid paint. This continues until finally, as with the limp loop-de-loop “Untitled (Bacchus)” (2005), the dripping drool becomes the sine qua none of old age and festive excess itself.

Well, at least it was a major whoop while it lasted.

Cy Twombly continues at the Centre Pompidou (Place Georges-Pompidou, 4th arrondissement, Paris, France) through April 24 and Cy Twombly: Orpheuscontinues at the Gagosian Gallery (4 Rue de Ponthieu, 8th arrondissement, Paris, France) through February 18.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario